Shahd Abusalama recounts her father Ismail’s experience in the Israeli prison system and calls for drastic reforms

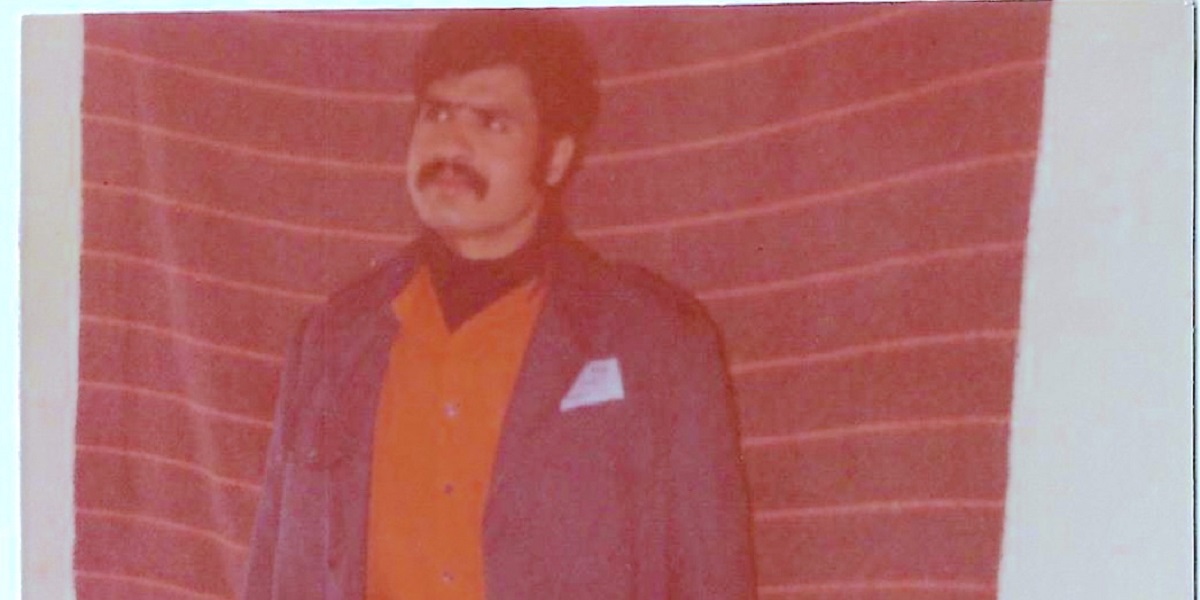

‘I was sentenced for seven lifetimes plus ten years and I thought that Nafha Prison would be my grave. Luckily I didn’t stay that long, and I was set free to marry your mother and to bring you to this life,’ my father says playfully. I struggle to understand this understatement of an experience inconceivable to most. He was 19 when he was arrested and spent 13 years in the Israeli prison system before his release in 1985. Thirteen years is only ‘not that long’ compared to his original sentence, which was suspended as part of a deal struck to exchange Palestinian and Israeli prisoners.

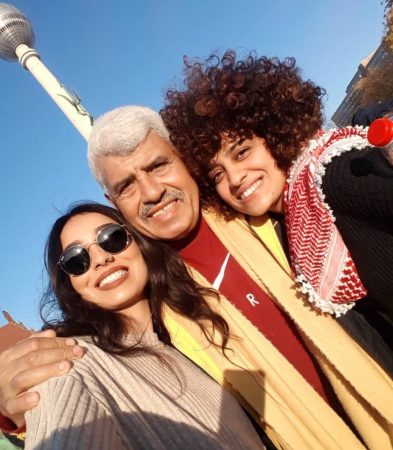

I can’t recall my father ever showing regret or sorrow for the years stolen from him. He believes that it is the basis for his solid principles, strong character, intimate friendships, and emancipatory outlook on life. I have always been proud to be his daughter and always will be. He is a revolutionary, and as a Palestinian refugee, revolutionary thinking has been an organic part of his upbringing.

He was born to a dispossessed family from Beit Jerja, four years after Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948, an event we call the Nakba (catastrophe). He grew up in Jabalia refugee camp where Israeli colonial oppression defined every aspect of daily life.

The triumphant power of revolution

He was arrested in Jabalia Camp on 23 January 1972. The German-Israeli lawyer Felicia Langer, in her book With My Own Eyes (1975), recorded the story of his capture: ‘They dragged him to the Gaza police station while beating him with batons all the way’. He was showered with extremely cold water and soldiers continued to attack him with batons all over, to the extent that he lost his sense of hearing. ‘This continued for ten days … Then they threatened that unless I talked I would be banished to Amman, where I would be killed,’ he told her.

Like many other Palestinians, my father was automatically tried at an Israeli military court, where the judges and prosecutors are Israeli soldiers in uniform. Palestinians are always somehow guilty for challenging the authority of the military occupation regime. According to Israeli human rights group B’tselem, Israeli military courts ‘are firmly entrenched on the Israeli side of the power imbalance, and serve as one of the central systems maintaining its control over the Palestinian people’.

On 30 November 1972, the prosecutor called on the court to wage a ‘serious war against terror’ and impose the harshest punishment on my father and his comrades who were all charged with belonging to the Marxist-leaning Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. According to Langer, the prosecutor claimed to be showing lenience in ‘not asking for death sentences’. Before issuing his verdict, the judge allowed my father and his comrades to say their parting words, but warned, ‘I don’t want to hear political speeches’. His comrade Abdel-Rahman, now the husband of my maternal aunt, said there was no point since they did not recognise Israeli jurisdiction. A riot erupted inside the courtroom and the defendants were prohibited from making further comments. In the middle of all this, my father shouted his belief in ‘the triumphant power of the revolution’ to achieve justice for them and Palestine. Despite a sentence that promised death in jail, he maintained his faith in a revolutionary end to his ordeal.

Prisoner exchange of 21 May 1985

He holds back tears while telling me the story of his eventual release. ‘I cannot forget the moment when the prisoners’ representative started calling out the names to be released,’ he says, with his eyes pinned to the painting he made during his imprisonment – flowers blooming and barbed wire among the names of his family.

The exchange process began after Ahmad Jibril of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC) captured three Israeli soldiers (Yosef Grof, Nissim Salem and Hezi Shai) during the First Lebanon War. Following a long negotiation, a deal was struck for Israel to release 1,150 prisoners in return for the three Israelis that Jibril held captive. My father was included in the deal and was set free at the age of 33. Among the other released prisoners was the Japanese Red Army revolutionary Kozo Okamoto, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment, and Ahmed Yassin, the founder of Hamas, who had been sentenced to 13 years in 1983.

The prisoner tasked with reading out the list of the released detainees was Jerusalem-born Omar al-Qasim, a leading member of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) who played a crucial role in the Palestinian Prisoners’ Movement from 1968 as one of the earliest Palestinian political prisoners. He was initially excited, hoping his freedom would be restored. Every time he said a name, a scream of happiness shook the prison walls. Gradually, his facial expression began to change, struggling to speak as he realised that his name was not included. My father thinks that this was a form of psychological torture staged by the Israeli prison warden. Al-Qassim died four years later of medical neglect in an Israeli cell after 31 years of captive resistance.

My father describes this emotionally-charged moment as bittersweet. The happiness of freed prisoners was incomplete for leaving the other prisoners in that horrible place where the sun never shines. ‘We were like a big family sharing everything together. We collectively handled the same pain and united to fight for one cause,’ he tells me. ‘Although I am free now, my soul will always be with my comrades who remain in there.’

History repeats itself. On 18 October 2011, we experienced a similar historical event with a prisoner exchange deal involving the Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who was arrested by the resistance while he was on top of an Israeli tank invading Gaza. Just like what happened with Shalit, the 1982 capture of three Israelis provoked an uproar from the Israeli public and the international media, but the thousands of Palestinian prisoners went unnoticed.

Administrative detention and resistance

The power imbalance between the occupying authority and the occupied people is always downplayed by international media coverage of such events. Israeli soldiers are portrayed as kidnapped by ‘terrorists’. Meanwhile, thousands of Palestinian political prisoners languish in Israeli jails with their basic rights to fair trial, medical care, and family or lawyer visits denied – not to mention the ever-present backdrop of Israeli settler-colonialism, siege and military occupation.

The plight of prisoners remains central to the Palestinian cause, especially given that Israel uses detention to crush resistance. Since the Nakba, over a million Palestinians have been subjected to imprisonment, including children. The occupying power justifies this use of administrative detention by claiming that it holds secret information. This is neither shared with the administrative detainees nor their lawyers, leaving many Palestinian prisoners in an inhumane limbo, never facing trial nor being formally charged.

My father has always said that ‘prisoners are the living martyrs’ and that Israeli jails are ‘graves for the living’. National protests demanding the liberation of all Palestinian prisoners were practically a mandatory part of my upbringing.

Despite the many injustices of captivity, the Palestinian Prisoners Movement has never been broken, with resistance efforts including organised hunger strikes. The stand taken by those detained inspires both within Palestine and around the world, especially given the strong sense of internationalism found in Palestine solidarity efforts. Angela Davis, for instance, recalled how ‘solidarity coming from Palestine was a very major source of courage’ during her imprisonment in the early 1970s.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shone a light on the rights of prisoners around the world. From the US to Palestine, many are seeing the institutional injustices of the prison industrial complex and the levels of profit being made, and have begun questioning this system much more critically than before . We are finally imagining the possibility of a world in which such institutions no longer exist. Now, more than ever, is the time to organise locally, nationally and internationally for the rights and freedom of Palestinian prisoners.

Their freedom will be a triumph for humanity.

Shahd Abusalama is a PhD student at Sheffield Hallam University, born and raised in Jabalia Refugee Camp, Gaza