![Ismail Abusalama and his comrades managed to survive their ordeal because they were convinced their 'cause is just' [Courtesy of Shahd Abusalama/Al Jazeera]](http://www.theprisonersdiaries.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/c06b8e41ffc44494b16f23cbea2229b9_18.jpg)

Ismail Abusalama and his comrades managed to survive their ordeal because they were convinced their ’cause is just’ [Courtesy of Shahd Abusalama/Al Jazeera]

Palestinian prisoners have engaged in hunger strikes as a nonviolent method of protest since 1968, after Israel occupied the remaining Palestinian territories of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. Some strikes have been regarded as successful, while others were seen to have failed to reach their goals.

Here, Palestinian activist and writer Shahd Abusalama reflects on her father’s experience participating in a mass hunger strike in an Israeli jail almost four decades ago.

READ MORE: What it means to be a Palestinian prisoner in Israel

“If we had not resisted through mass hunger strikes, we would have remained like the slaves from the Middle Ages,” my father, Ismail, told me during a Skype call after I forced him to revisit his memories from the 33-day legendary Nafha prison hunger strike that he joined 37 years ago.

His memories sounded shockingly vivid and descriptive, given how distant they are. His eyes were fixed to the ceiling of his room at home in Gaza while he continuously scratched his chin as though he could picture everything he was narrating. His body language evoked a suppressed anxiety.

In 1980, my then 27-year-old father had been in Israeli jails for 10 years, which seemed trivial compared with the seven lifetime sentences he had been given for his affiliation with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) group.

He would have ultimately ended his days in Israeli prisons, had he not been part of the 1985 prisoner exchange.

READ MORE: Palestinian hunger strikers – ‘They had no choice’

He was one of 80 Palestinian political prisoners who had been transferred to the then recently opened Nafha prison in the Naqab (Negev). Conditions were extremely harsh.

| Nine days into our strike, 26 of our comrades were forced into a steel cell on a truck, sprayed with gas, and taken on what seemed like a death journey to an unknown location. |

It was located in the desert – one kilometre above sea level – “which meant that it was boiling hot in the summer and freezing cold in the winter,” my father recalled.

“It consisted of narrow cells that hardly saw the sun; each had a partially covered narrow rectangular window just below the ceiling and a metal door with a small aperture externally controlled by the prison guards.

“Each cell, that would normally be suitable for two, was packed with eight prisoners; we were allowed only a half-hour walk per day outside these cells in a yard that was less than 400 square metres and had a barbed wire ceiling. We were not allowed to walk in groups; only as individuals or at most in pairs, and we just walked in circles under the hard gaze of Israeli soldiers.”

The Israeli authorities had chosen the 80 detainees transferred to Nafha from among thousands of Palestinian prisoners. The 80 were deemed to be the most stubborn detainees.

The Israel Prison Service (IPS) had assumed that moving the prisoners for “disciplinary” reasons would break their resistance. The prisoners themselves feared that the success of this “disciplinary” action would mean that “all detainees’ achievements prior to 1980 were void” and would create a precedent to be applied to other Palestinians under detention.

“So, from day one in Nafha prison, we realised that we had to prepare ourselves to counteract this oppression,” my father said. “The alternative was a death sentence.”

In the run-up to the strike, the detainees drafted a list of demands and submitted it to the prison administration. Most of those demands were rejected. “At that point, we realised that a hunger strike was our only resort,” he said.

The prisoners launched their hunger strike on July 14, the date on which the Bastille Prison was stormed at the start of the 1789 French revolution. That was the idea of Omar al-Qassem, a leading member of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP). Qassem died in prison in 1989; he had been locked up by Israel for 21 years.

|

| Former Palestinian hunger striker Ismail Abusalama with his wife [Courtesy of Shahd Abusalama/Al Jazeera] |

The demands made by my father and his comrades were very similar to those of the open hunger strike that over a thousand Palestinian prisoners launched on April 17. They are all related to essential human rights that Israel has persistently violated.

The demands were an end to collective and individual punishment, particularly the use of solitary confinement, the replacement of the pieces of sponge for sleeping with proper beds, blankets, winter and summer clothes, bimonthly family visits, access to food items in the prison canteen on an equal footing with Jewish prisoners, access to newspapers and books, expansion of cell windows and extending the daily outdoor walk to an hour.

Although the demands were simple, my dad pointed out how vital they were for someone locked up in a cell indefinitely and existing in basic survival mode.

Whenever Palestinian prisoners have gone on hunger strike, the Israeli authorities have responded by punishing them collectively. The Nafha hunger strike was no exception.

|

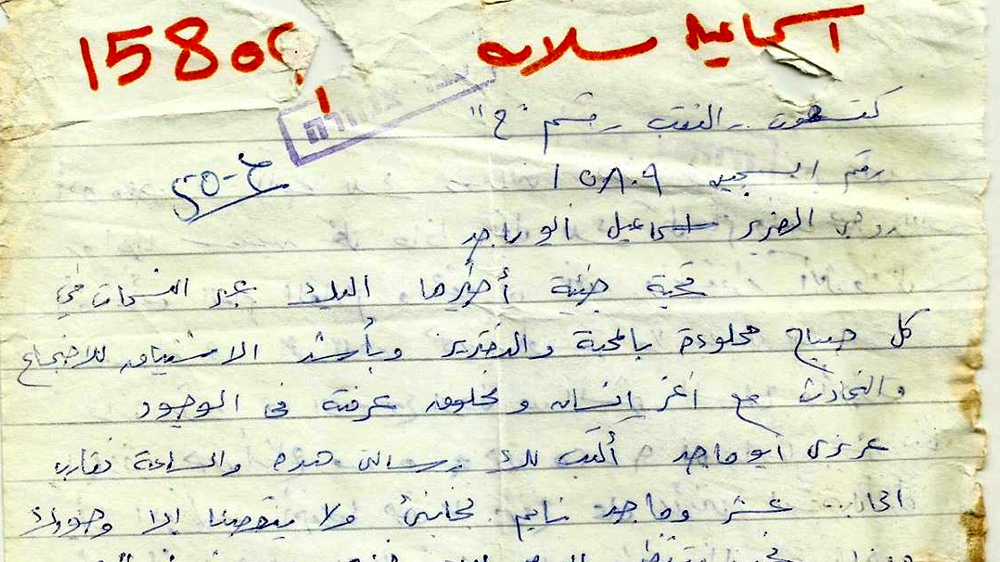

| ‘I write this letter to you while our son Majed sleeps next to me. Your presence is the only thing that we’re missing,’reads a letter written by Ismail Abusalama’s wife and sent to him while he was in detention [Courtesy of Ismail Abusalama/Al Jazeera] |

“Nine days into our strike, 26 of our comrades were forced into a steel cell on a truck, sprayed with gas, and taken on what seemed like a death journey to an unknown location,” my father said. That location was later identified as a prison in Ramla, a city in present-day Israel.

The gas made the prisoners – who were handcuffed and had their legs shackled – cough throughout the journey. In Ramla, the Palestinians “were ‘welcomed’ by Israeli prison guards queuing on both sides, who beat them with batons as they walked through [the prison],” my dad said. The beatings continued even as the prisoners changed into the uniforms they were forced to wear.

Among those 26 prisoners were Rasem Halawa, Ali al-Jafari and Isaac Maragha, who died as a result of force-feeding in the prison’s clinic a few days later.

There were several attempts to force the 26 prisoners “to break our hunger strike”, my father said. “But they [Israeli prison authorities] neither succeeded with those 26 prisoners, nor with the rest of us. We responded with more stubbornness, until we reached the long-awaited victory, 33 days later.”

The IPS has consistently resorted to force-feeding Palestinian hunger strikers despite the practice being banned by the Israeli High Court of Justice. Israeli Minister of Public Security Gilad Erdan has been campaigning to revoke the ban to legitimise the use of force-feeding to prevent future hunger strikes, which he has described as “a new sort of suicide bombing to threaten the state of Israel”.

Some Israeli doctors have refused to engage in force-feeding on the grounds that it is “unethical”. Israel is considering hiring foreign doctors to potentially force-feed hunger strikers under the pretext of “protecting” their lives.

INFOGRAPHIC: A timeline of Palestinian mass hunger strikes in Israel

After 18 days of refusing food, my father was forced to choose between eating or a device known as the “zonda”, a device consisting of a container and a long tube that could stretch from the nose or mouth down to the stomach.

The “zonda” was dirty and “any mistake carried the risk of death”, my father said. “It looked as if it had just been dipped in sewage. It was used on successive prisoners without being cleaned. The prison guards thought it was an effective way to disgust prisoners enough to accept food.”

My dad resisted the psychological warfare, at which point an Israeli nurse force-fed him while his hands and feet were chained to a chair.

How did my father and his comrades survive their ordeal? They managed to because they were convinced that their “cause is just” and because the support they received from people outside the prison “fed our determination”, he said.

My father stands with the Palestinians now refusing food. Every day, he goes to a tent in Gaza that has been erected in solidarity with the hunger strikers.

International campaigning is vital to “make the detainees’ battle for dignity shorter,” my father believes. “The frequency of hunger strikes in Israeli jails is a testament of their desperation.”