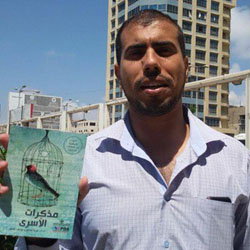

I interview Abdul Menim Aabed, 27- See more at: https://wearenotnumbers.org/home/Story/Boat_from_Gaza_attempts_to_break_Israeli_blockade

Abdul Menim Aabed, 27, is among a crowd of Gazan Palestinians who are anxious—despite the obvious danger—to be among the first to try to sail out of Gaza tomorrow on Al-Hurriyah (Liberty). The boat is being organized by the Great Return March National Organizing Committee and will carry 35 Gazans who hope to receive medical treatment or to study abroad.

“I can’t walk right anymore and I can’t get the treatment I need here in Gaza,” says the wheelchair-bound Aabed, who was shot in both legs at the border protest May 4. “I’m desperate.”

The plan for the requisitioned fishing boat is to attempt its departure on May 29, the eighth anniversary of the Israeli attack on the Turkish boat Mavi Marmara, one of the ships in the Gaza Freedom Flotilla that tried to break through the blockade. When Israeli troops halted the flotilla in international waters in the Mediterranean Sea, nine activists were killed. The international outrage that followed forced the Israeli government to ease the blockade somewhat by allowing more goods into Gaza, but it has remained in place.

Protest organizers have warned potential passengers it is likely the Al-Hurriyah will be attacked by the Israeli navy and they could be arrested as well. Still, Aabed and others are lining up to register for this first attempted voyage or for others that will follow.

Another hopeful passenger is Kamal Elias Tarazi, a Palestinian from Bethlehem who traveled through Egypt to Gaza to visit family members in 2012 and has been stuck there ever since, despite repeated attempts to leave.

“My health is bad and I want to go home,” he says. “I’ve tried to leave through [Egypt’s] Rafah crossing dozens of times, but they refuse to let me out.”

Egypt has opened the Rafah crossing for the duration of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, temporarily easing the border blockade of Gaza enforced by Israel for the past 12 years. But more than 20,000 residents hoping to travel are on the waiting list, a backlog created by long periods of closure, and Egyptian border officials are clearing about 400 travelers attempting to leave a day, about a third of the usual volume in past years.

For those with money, there’s also the option of what Gaza residents sarcastically call “Egyptian coordination.” This refers to payments, reportedly up to $3,000 per traveler, to Palestinian middlemen who claim to have connections on the Egyptian side. Few Gazans have that kind of money, however, and sometimes these middlemen simply pocket the fee without producing any results.

Permits are even more difficult to obtain to travel out of Gaza via the Israeli Erez exit. In April, for example, only about half of all requests by to leave for urgent health care were approved.

Holding a poster thanking Turkey and other countries for being willing to accept Palestinians, Tarazi didn’t seem scared about attempting to travel by boats since he has “tried all other means to get out. I don’t care if these boats are hit by the Israeli army. I have to try everything to get treatment and go back home to Bethlehem.”

Tarazi’s message to the world is the same as that of all of Gazans interviewed: to help break the Israeli siege.

“We have thousands of injured people here in Gaza and they must get treatment outside Gaza,” he says.

Yousef Abu Arish, director general for the Gaza Ministry of Health, said at a news conference that the health care system in the Strip is unable to deal with the large number of wounded (more than 13,000 to date) from the Great Return March.

“We’re working in inhumane conditions in terms of the extent of the injuries and the number of wounded being brought in at the same time to the shock room and the operating rooms. As skilled as the staff is and as much as they want to help the victims, in the end they’ll collapse under the burden,” Mahmoud Matar, MD, a specialist in orthopedics at Shifa Hospital in Gaza City told the Haaretz newspaper.

Adnan al-Barash, MD, added that surgeons are seeing complex injuries, including bullet-exit wounds 15 centimeters wide. “There’s no question the Israeli army is using bullets and other very dangerous weapons that leave very complex injuries requiring prolonged treatment, which the health care system in Gaza is unable to provide,” he said.

The attempt to address this crisis by sailing a boat out of Gaza comes one week after the launch of a three-ship flotilla attempting to break the Israeli blockade from the outside. The group includes a fishing boat owned by the Freedom Flotilla Coalition named Al-Awda (Arabic for return), which left the Norwegian port of Bergen April 30, and three ships sponsored by Sweden’s Ship to Gaza movement–the Heria (another English spelling for the Arabic word for freedom, or liberty), Falestine (Palestine) and Mairead (after the Irish Nobel Peace Prize laureate and BDS activist Mairead Maguire, who was on board the 2010 flotilla in which the Mavi Marmara participated). Although the Free Gaza Movement successfully sailed five times into Gaza, all flotillas since 2008 have been forcibly stopped by the Israeli navy.

Israeli aircraft targeted and destroyed a boat May 23 in the Gaza City harbor that had been due to sail to meet this latest flotilla should it actually succeed.

“Gaza has become a big prison isolated from the world. The Palestinians of Gaza are banned from the exercising the simplest of human rights due to the Israeli siege,” said Salah Abdul Atti, a member of coordination committee for the Great Return March, when the attempt to sail out was announced. No further details on the boat or the first round of selected passengers were released, to try to protect them from Israeli reprisal.

During the press conference, students, injured people, children and others held posters saying, ‘’We dream to have a seaport’’ and “We are waiting for your ships and delegations to break the Israeli siege on Gaza.’’ One group held pictures of the nine passengers who were killed during the Israeli attack on the Mavi Marmara.

Ismail Ridwan, a leader with the Hamas government, noted, “Our case [against Israel] is political, and humanitarian cases should not be linked to political debate because health care and education are basic human rights.”

One 60-year-old woman who refused to give her name attended, even though she is too sick to travel by boat. Nevertheless, she said she came to the seaport to “support and encourage those who will participate so we can break the siege that is suffocating us.”