Dozens of children remain in detention amid the Covid-19 pandemic. They must be released to their families immediately

Palestinian children walk past a mural depicting the coronavirus and a prison cell in Gaza City on 28 April (AFP)

Iheard the chains before I saw them enter. Four teenage boys shackled together by the wrists and ankles shuffled into the defendants’ box in the small courtroom.

One of them, Ahmed*, looked particularly young, as he stood on tiptoes to peer over the edge of the box. He was accused of throwing a stone, a charge he denies, and was waiting to hear a verdict from the military court.

The boys’ short trials – at most five minutes each – were held entirely in Hebrew, with a soldier occasionally translating the odd word into Arabic for them. The boys looked scared and confused as they awaited their fate. They kept trying to speak to their lawyers, but this was not allowed.

Desperate gaze

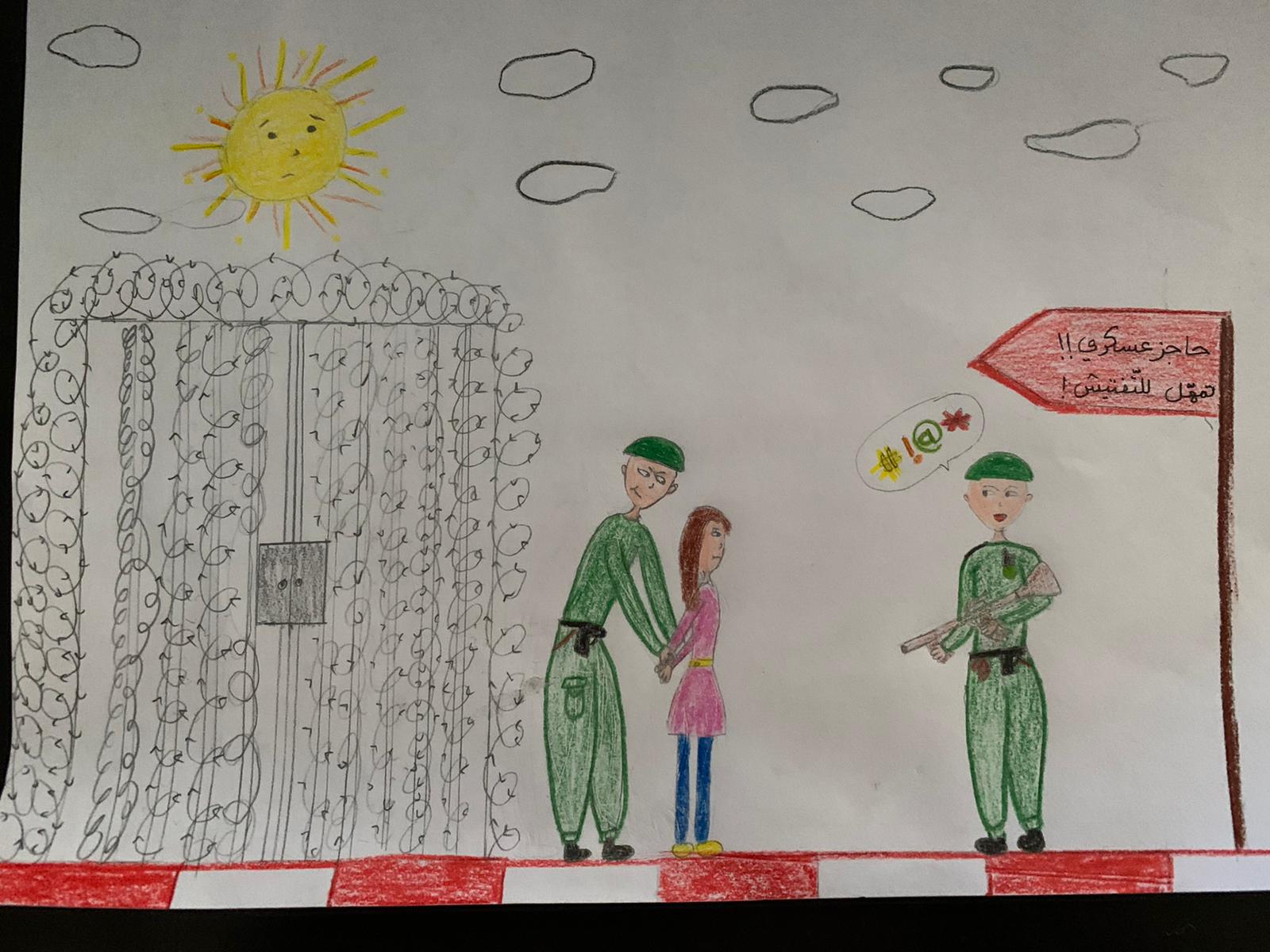

I was at the Ofer military court in the occupied West Bank in February, watching the trials of Palestinian civilians by Israeli military judges. This court system does not apply to Israeli children, who are instead governed by civil law – as is the case for most children around the world.

When Ahmed’s time came, it was decided that there was additional evidence to bring, so he would need a retrial. Ahmed looked desperately at his father, Munther*, who was sitting next to me, as he was chained before being taken back to prison.

Munther was handed an information sheet in Hebrew that he could not read. As he was leaving, Munther said that he felt like he was abandoning his son: “I just don’t know how to help him.”

Each year, around 500-700 Palestinian children are detained and prosecuted in the Israeli military court system. The most common charge is stone-throwing, for which the maximum sentence is 20 years. Currently, more than 190 Palestinian children remain in detention in Israeli prisons – the majority of whom, like Ahmed, are in pretrial detention and have not been convicted of any offence, despite calls by the United Nations to release them before coronavirus spreads.

Horrific conditions

Former child detainees have told us that the conditions in which they are held in Israeli prisons are horrific, with overcrowded cells, few available sanitary products and almost no access to medical assistance.

Loai*, 18, was released at the end of April after three months in jail. He was 17 when he was incarcerated and shared his cell with five other children.

‘They did not disinfect our cells, not even once. They gave us a bottle of disinfectant that lasted about 15 days, and they never gave us more after it ran out’ – Loai*, former child detainee

When the coronavirus pandemic started, he said the children were not informed: “We weren’t told anything about how to keep ourselves safe from coronavirus, such as how it’s important to wash our hands.” Still, the prison’s rules changed: “Now, children are only allowed out for an hour each day.”

Throughout his detention, Loai said, “the prison guards disinfected the facilities twice only. They disinfected the showers, the stairs and the corridor. They did not disinfect our cells, not even once. They gave us a bottle of disinfectant that lasted about 15 days, and they never gave us more after it ran out.”

Inadequate food and water

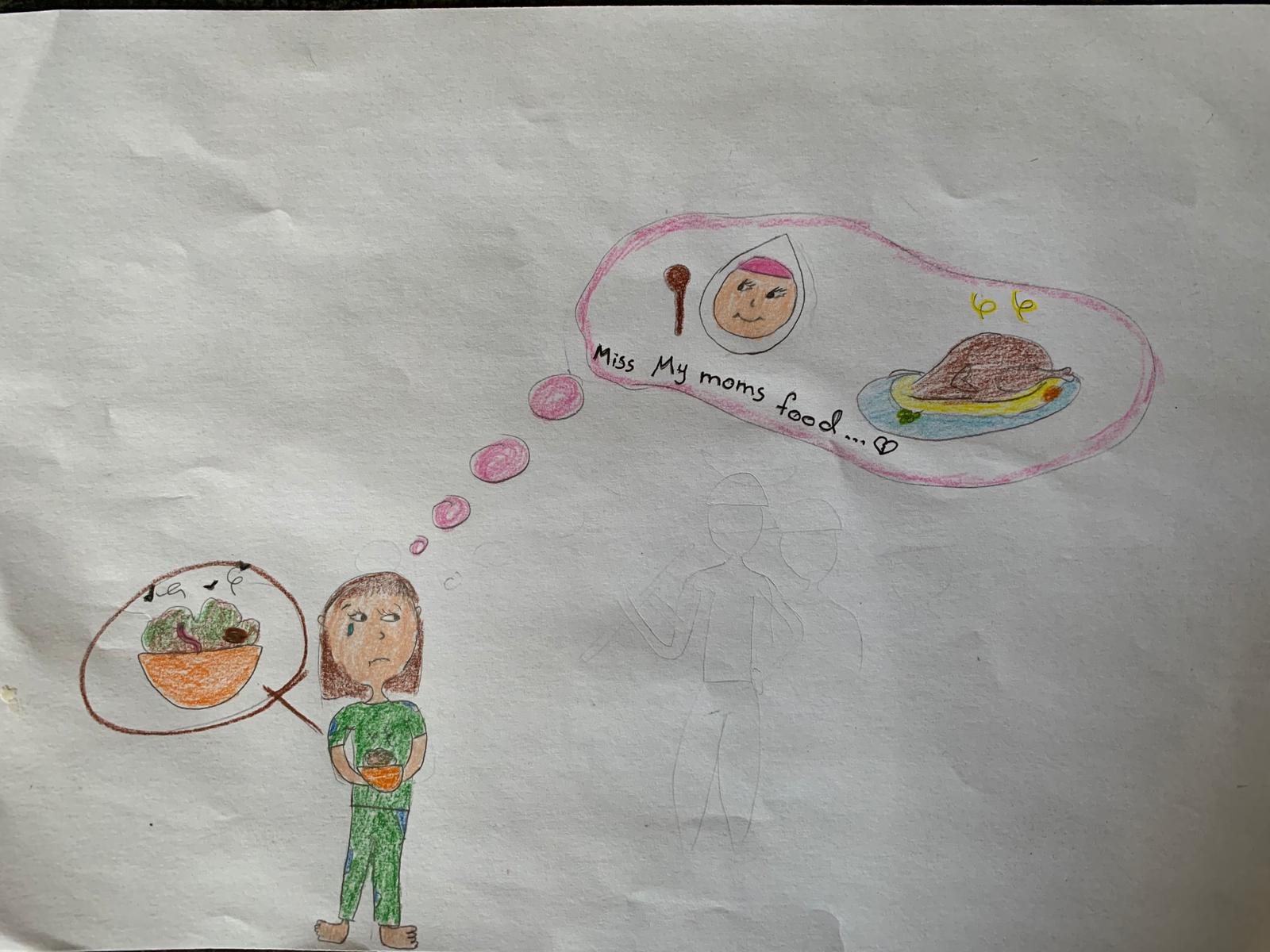

Heba* was arrested when she was only 14, and she was detained for eight months. Three years later, she is now preparing for her school exams, but vividly remembers her time in prison.

“We were five girls in one room; the eldest was 17 years old, and I was the youngest. The prison cells barely fit two people. We could not move around in them. There was a toilet with no door. Cockroaches swarmed everywhere in the summer. There was no window for ventilation, and the room was very dark.”

Heba and her fellow detainees were not provided with any sanitary products, which they had to buy themselves from the prison shop. “Water was barely drinkable. It was white, and the chlorine smell in it was really strong,” she added.

“The food wasn’t fit for humans. For example, when they gave us chicken once a week, it still had its feathers on it and wasn’t properly cooked, with blood inside,” she said.

But the toughest part was the limited family visits. “My parents were allowed to visit me three times only during my eight-month detention,” Heba said.

Since the coronavirus pandemic erupted, visitation rights have been suspended by Israeli authorities, with dozens of families unable to visit their detained children. According to current rules, children can make a 10-minute phone call to their family every two weeks – but in practice, most only get to speak with their families once a month. The toll this prolonged isolation takes on their wellbeing cannot be overstated.

Window of opportunity

Alaa*, 17, echoes Loai and Heba when recalling his six months in jail: “We tried to clean and disinfect the place every day, but then the guards would enter our rooms with their dirty boots and dogs about five times a day. Phone calls to my parents were not allowed. I was really frustrated and in desperate need to contact my mum, dad and siblings.”

Palestinian children detained in Israeli prisons are enduring the precise conditions health experts have warned against in the fight against coronavirus. In addition to the huge risk to their health and potential undermining of efforts to contain the spread of the virus, many children are stuck in limbo – cut off from their families, unaware of what their future will hold or even when their cases may be heard.

We cannot afford to abandon these children. There is still a window of opportunity to bring them home; to protect their right to health, control the outbreak and avoid further suffering.

All Palestinian children who can safely return to their families and communities should be immediately released. Israeli authorities should place a moratorium on new admissions and safeguard the rights of children who remain in detention, protecting them from violence, abuse and exploitation.

*All names have been changed for privacy reasons.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.